- January 14, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

I was only 23 years old — just one year into my job as a staff writer for the East County Observer, which covers Manatee and Sarasota counties. I got into hyperlocal community news specifically because I had no desire to cover national or international news.

And, when I pulled up to Emma Booker Elementary School in Sarasota that morning — Sept. 11, 2001 — to hear President George W. Bush speak, it was supposed to be a lighthearted affair — a puff piece about his education initiatives. Earlier that week, my colleagues at the Longboat Observer waited anxiously for the president’s motorcade to pass the office; my wife (and then girlfriend) Jess Eng got starstruck and dropped her camera to wave. We were all buzzing with excitement to have the president spending time in our little community. We were naïve — and so, so sheltered.

My 9/11 started way earlier than I wanted. The East County Observer went to press on Monday nights. As a cub reporter, Tuesdays were relatively light days I used to set up interviews for the following week.

But, with Bush in town, my editor thought it would be good experience for me to attend the press briefing. The week before, I called the White House and requested press passes.

One phone call. That’s all it took to get into the same room with the president.

Of course, the government wanted all the press in place well before Bush’s scheduled statement at 9:30 a.m. I pulled into Booker before 7 a.m. and walked through a metal detector and received my credentials.

“Sept. 11, 2001,” they read. “Trip to the president.”

That’s all it was supposed to be.

Within seconds of American Airlines Flight 11 striking 1 World Trade Center, reporters’ cell phones started erupting into a chorus of ringtones.

The first report: A Cessna has hit the World Trade Center.

Strange, we all thought.

But then, calls kept coming. No, not a Cessna. Something bigger. A commercial plane.

By 9 a.m., we all were huddled into a storage room where the school kept its audio/visual equipment.

There was one TV on.

We watched — over and over again — that first plane. Then, the second plane. Over and over again. It looked fake — like something out of a Michael Bay flick. The planes simply disappeared into the building and an orange fireball. The room, crammed with at least 40 people whose profession was communication, was silent.

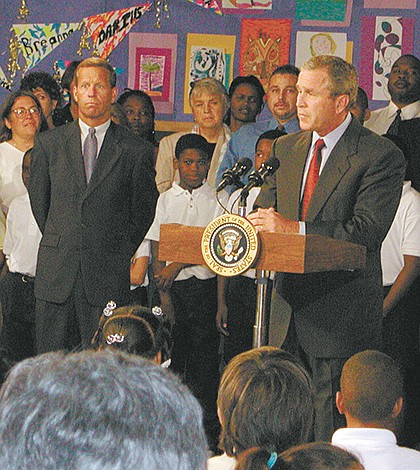

At precisely 9:30 a.m., Bush emerged to take the podium. The school had assembled a backdrop of students and teachers. Student artwork hung on the back wall. Some of the students grinned brightly for the cameras. Bush folded his hands at the podium.

“Today, we’ve had a national tragedy,” Bush said. “Two airplanes have crashed into the World Trade Center in an apparent terrorist attack on our country.”

With my left hand, I held up my tiny digital point-and-click, firing shot after shot as quickly as it would allow. With my right hand, I steadied my notepad on my knee as my pen attempted to capture every word.

Bush was in and out in less than five minutes.

I rushed back to the office with my notes and photos. By the time I arrived, the South Tower had collapsed. The Longboat Observer was going to press that afternoon, and fellow reporter Mischa Viera and I were tasked with working on a story for their deadline. My editor ran to Walmart to buy a television for the office, and Mischa and I cobbled together what we could.

By that afternoon, I must have seen those buildings collapse thousands of times. That day was relentless. I thought the sun would never set.

After Longboat went to press, I called their designer — my future wife. Neither of us wanted to go home.

Do you want to go have dinner? I asked.

We huddled in the corner of a Cracker Barrel restaurant — the most American place we could find that day. There were no TVs, no websites, no replays.

We didn’t talk much, but it was comforting just to be with each other. We both knew the world — as we knew it yesterday — was gone.