- April 4, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

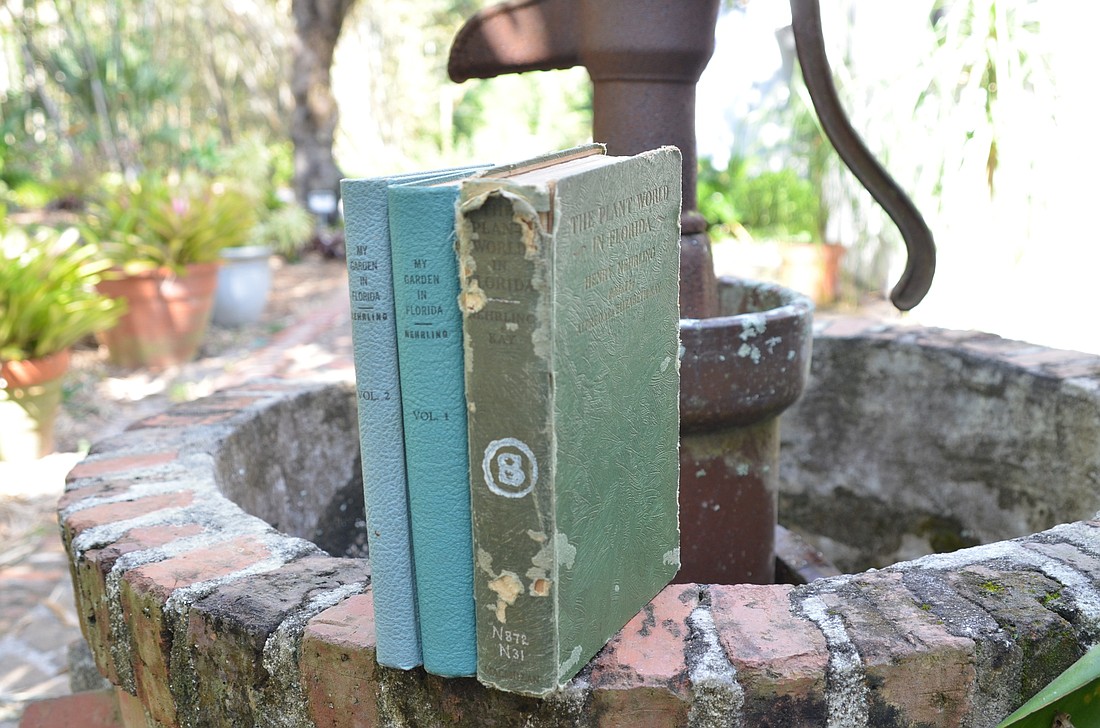

Theresa Schretzmann-Myers first applied for a $59,000 matching grant to renovate the old homestead that stood watch over the grounds of Gotha’s Nehrling Gardens in 2017. The original application package for a restoration project included beautiful photos of the gardens.

But then Hurricane Irma struck Central Florida, leaving behind a path of destruction — and forcing the postponement of the grant award in Tallahassee.

“After the hurricane hit, they told everybody, ‘We need you to dig out from the hurricane and come back,’” Schretzmann-Myers said.

“We were devastated,” she said. “The gardens were looking great, and we basically had to start over.”

For Nehrling Gardens, that meant spending an extra $18,000 to clean up. The five-story bunya tree lost two-fifths of its height, the top crashing down on a historic palm. A massive tree in the neighboring yard blocked the Nehrling Gardens driveway and punctured the roof of the garage classroom wing. The cost to remove this tree was $4,000.

Schretzmann-Myers said a tornado touched down near Lake Nally to the east, uprooted a giant magnolia and sent an oak tree into the greenhouse before striking the bunya tree. Some of these trees were 60 inches in diameter.

“It took us six months to a year to recover from Hurricane Irma,” she said.

Earlier this year, Schretzmann-Myers and a construction representative from Austin Historical, in Orlando, returned to Tallahassee to appear in front of the Florida Historical Commission. They had six minutes to plead their case in hopes of winning the large grant.

Nehrling Gardens applied for the special-categories grant to remove all the rotted wood off the house and kitchen and replace the rotted wood siding and any rotted timbers with new pressure-treated pine. The rest of all the original wood will be kept, Schretzmann-Myers said, but the lead paint will be carefully removed using an environmentally friendly liquid that congeals into one layer and can be peeled away.

She said the commission chair was excited to hear about the Nehrling project. After all the applications had been presented, Nehrling was ranked No. 4 out of 61.

“We knew that we would definitely get that matching funding,” Schretzmann-Myers said.

Nehrling Gardens raised the matching dollars through plant sales, the annual wine walk and amaryllis festival and other community outreach efforts.

THIS OLD HOUSE

Schretzmann-Myers explained the detailed restoration project.

“We’re removing all the rotted wood from the historic house, the front and back porch and the historic kitchen and replacing it with new pressure-treated pine or heart pine and/or accoya wood,” she said. “We are also restoring the metal roof; pressuring cleaning and getting all the algae off, stopping the rust and corrosion. We have to repoint all the brick work — chimney, brick pier foundations under the house, the front porch.”

As part of the grant, Schretzmann-Myers must document all the work in photos.

“It’s a great way to show how you can reuse these homes and not tear them down and start over,” she said. “Beautiful craftsmanship, sure they need a little TLC, but the workmanship is beautiful. It’s part of our Florida history and our architecture.”

Work began Jan. 29. The Frame Vernacular architecture was a popular design for homes built in West Orange County in the 1880s.

As work continues on the home restoration, the gardens continue to serve as a tool for getting students outside and teaching them science. And so many of Nehrling’s trees still stand.

“Robins come in to eat the cherries from all the cherry laurels and the Surinam cherries and the palm nuts that he planted,” Schretzmann-Myers said. “The palm warblers come in to eat the palm nuts and seeds. We have cardinals and tufted titmice, mockingbirds and the water birds at the lake. We have owls that live here year-round in trees Nehrling planted. Every Florida-native tree or palm feeds a bird.”

And while the process is tedious, Schretzmann-Myers is grateful for the chance to learn more about the gardens and the property’s history.

“You get to see every historical document ever filed for this site, starting with when it first applied for National Register status,” she said.

The organization has two years to complete the project.