- December 13, 2025

-

-

Loading

Loading

It’s often said you can tell a lot about a person by his shoes.

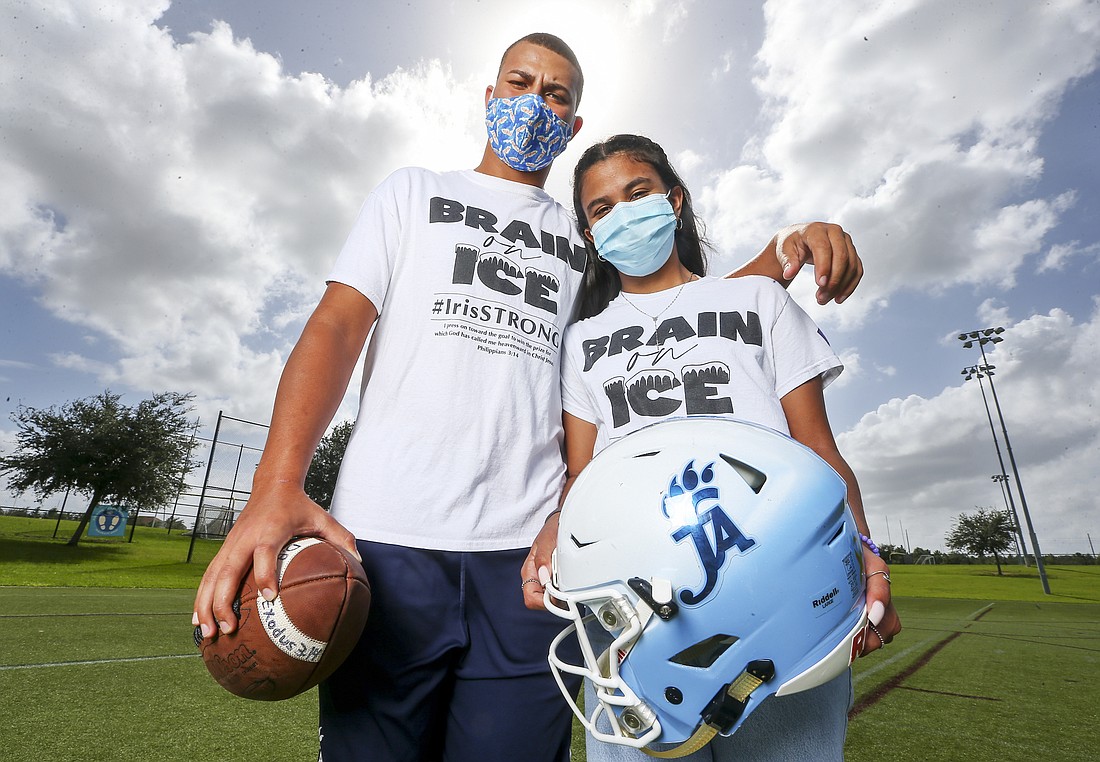

If that old adage holds any truth, then Daniel Rosado’s football cleats tell the story of a young man fighting on the field for both his team and his sister — Iris Rosado.

A couple of weeks prior to the Foundation Academy football team’s season-opener, Daniel Rosado reached out to a friend at East Ridge — the school from which he transferred in January. That friend, a former teammate, always had customized cleats for every occasion.

But Daniel Rosado wasn’t just looking for any old design. He wanted a design to honor his sister who, since April, has been battling anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis, a rare autoimmune disease.

“I knew the first game of the season I wanted to do something somewhat special,” he said. “I knew it was my Senior Night, and I knew it was the first game Iris was going to see me play in a while. So I reached out to him and I said, ‘Hey, let’s get a pair of cleats, glitter them out in blue, put my sister’s logo in the back and then have them say Brain on Ice and #IrisStrong on the front.’”

The logo — which he created while Iris was in the hospital — is a ribbon that is half black-and-white zebra print and half purple. The zebra print pattern represents NMDA, while the purple represents epilepsy.

Daniel Rosado didn’t let onto the surprise but told Iris Rosado, 14, he had something in store for her — which was met by a sort of skepticism.

“He had told me he had done something for me, but usually when he says that, it’s usually because he’s taken something from me or he is going to prank me or something,” Iris Rosado said. “I think it was two weeks ago, he came inside the house and told me he had something for me and he showed me the cleats, and it was pretty awesome.”

On a regular Thursday in April, the Rosados were going about their life with a normal fashion. Then, the unexpected happen.

Omaira Rosado — Daniel and Iris Rosado’s mother — was sitting downstairs when she heard a loud “thump.” That sound was Iris Rosado walking into a wall in her bedroom because of an awareness seizure. She was taken to the hospital to be tested for COVID-19 and then sent home.

“I felt normal, but my mom questioned me after I ran into the wall, and I didn’t realize anything that was wrong,” Iris Rosado said.

Daniel Rosado remembers being at his then-girlfriend’s house when he got the frantic phone call from his mother about what had happened. She was hyperventilating and crying, and he thought maybe something had happened to his dad — he never guessed his sister had a seizure. He rushed to Southlake Hospital — beating the ambulance that was carrying his sister.

“I never got to see Iris when she was admitted, because my mom got there the same time as the ambulance, so they only allowed my mom in considering I wasn’t the parent and I wasn’t 18,” Daniel Rosado said.

“I knew the first game of the season I wanted to do something somewhat special. I knew it was my Senior Night, and I knew it was the first game Iris was going to see me play in a while.”

— Daniel Rosado on his custom cleats

After she was released the following day — Friday, April 17 — Iris Rosado had a grand mal seizure that caused her to stop breathing for about 15 seconds. She was taken to Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Hospital, but her tests came back normal. After a second visit to Arnold Palmer — due to psychotic behavior — Iris Rosado was treated with medication, but there was still no diagnosis. However, results from a spinal tap that was done eventually revealed that she had what was called anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis — the diagnosis came in on Saturday, May 2.

The rare autoimmune disease affects only two in every 1,000,000 people, and it’s caused by a person’s own antibodies attacking the body.

“Her cells produced these antibodies, and what they do is they attack the receptors of her brain, so it causes her brain to go ‘on fire,’ which means her brain tries to fight,” Omaira Rosado said. “The brain goes on fire, because it doesn’t know how to fight its own people inside the body, and then the antibodies fight the brain as if that part of her body does not belong there.”

The side effects of this specific disorder include psychotic behavior, hallucinations and the inability to speak and walk — all things Iris Rosado has experienced. Daniel Rosado recalled it being like she was dealing with split-personality disorder, but for Iris Rosado, it was like dealing with a constant case of déjà vu.

“I would lose track of everything, and my mind would go and think of other things and go blank, and I would just lose focus,” Iris Rosado said. “It felt like déjà vu. I was dizzy, and it was like I was thinking about multiple things.”

Iris Rosado was placed in the ICU At Arnold Palmer and immediately started treatment the day of her diagnosis. She was there from from May 1-11. There, she had a transplant of antibodies — known as a plasmapheresis — to remove the bad antibodies from her body.

Since her diagnosis, Iris Rosado has been taking different medications to help her deal with the disorder. She also has undergone intravenous immunoglobulin therapy on a monthly basis — which will last a full year. The medicines make her tired, and she doesn’t do as much as she used to, but they have helped her relax, she said. And there’s hope that the disorder can right itself, as anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis is reversible.

For Daniel Rosado, this year has been stressful and difficult, but there’s also been the silver lining of growing closer to his sister — to whom he has dedicated his final year of high school football. Things won’t be easy, but he knows the fight now is worth the effort.

“In certain aspects, it was (difficult),” Daniel Rosado said. “Mentally, it was hard to bounce back into the game, but at the exact same time — even though my mind was on other things — it was a big relief for me to finally be able to get the feeling of putting on the helmet.”