- December 22, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

Longtime industrial arts teacher Rudy Zubricky feels satisfaction when he learns his former West Orange High School students have made a career out of working with their hands.

Students such as Dino Angry, who owns a boat-repair business; or Vince Ragone and Bryan Emond, who run a landscape company; and Paul Watson, whose business exports pressure-treated lumber.

Another student, highway patrol officer Quincy Linan, built his own home in Groveland with the help of friends and Zubricky.

After more than three decades, Zubricky, who also has led the school’s bowling team to numerous victories in 28 years, is retiring. His last official day with OCPS is June 30.

In1986, Orange County Public Schools offered Zubricky, then living in Pittsburgh, a job leading the industrial arts program at one of four schools: West Orange and Boone high schools or Meadowbrook and Robinswood middle schools. WOHS hired him, and that is where he would spend his entire teaching career.

HANDS-ON KIDS

Zubricky said he grew up using his hands to build some kind of contraption or work on his car. After he graduated from high school, his mother, an English teacher, pressed him to choose a career and suggested he become a shop teacher. He enrolled in the local college in Pittsburgh, majoring in and earning a degree in industrial arts education.

After his graduation, OCPS had recruiters in the area; Zubricky had interviews in Pittsburgh and Orlando and was offered the position at all four schools. He landed at WOHS.

“I’ve taught the same thing all these years,” Zubricky said. “The position was technology education, specifically the materials processes, which is basically woodshop. And I’ve done the same thing, (although) I tried to change with the times.”

Zubricky said he instructs students on how to make many of the same projects he taught several decades ago.

“I tell the kids now, 10, 20, 30 years from now, you’re going to have some of this stuff and you’re going to be proud,” he said. “You know when you give this thing to your parents, they’re going to think it’s the greatest thing since sliced cheese. Some of the parents don’t know how to do this stuff.”

Students leave his classroom with the knowledge of how to build checker boards, step ladders and tables out of wood and how to weld a waterproof box or stool.

As equipment changed and improved throughout his career, Zubricky altered his teaching methods.

“Probably the biggest change has been the CNC machinery, computer numerical control machines,” he said. “If you had a router, there’s a router and a computer controls it. … The table saw has what we have ‘saw stop’ – it has a little computer. There are people with 10 digits because of that machine.”

Many “mishap” stories have floated around the shop classroom in three-and-one-half decades, and no matter how many safety talks Zubricky has had with students, there were bound to be those who wanted to test the system.

One student threw his hand into a blade to see if the “saw stop” would actually work. Another put his head in a vise, and still another tried to stop a router blade with his thumb and forefinger. Each of them earned a place of “honor” on the Wall of Shame, an area in the woodshop class with about 30 students’ names carved into wooden plaques and hung to serve as a lesson for the rest of the students.

“The Wall of Shame was a good teaching tool, and it made me remember how to teach certain things,” Zubricky said. “I would see that name and remember, ‘He cut his left finger cutting like this,’ so I taught it a different way. … If it prevents an accident — the kids’ safety is the No. 1 priority.”

Students respected Zubricky, and it is evident in the messages he receives from many of them.

“I still get texts from kids that say, ‘Hey, Z, check out this boat that I Fiberglased,’ ‘look at what I made,’” he said. “I get a bunch — kids (who) have graduated that do a variety of different things and they text me. Of course, you remember the kids who had talent and they show that they still have it. I have students who graduated in the ’90s come back and visit.”

THE PERFECT GAME

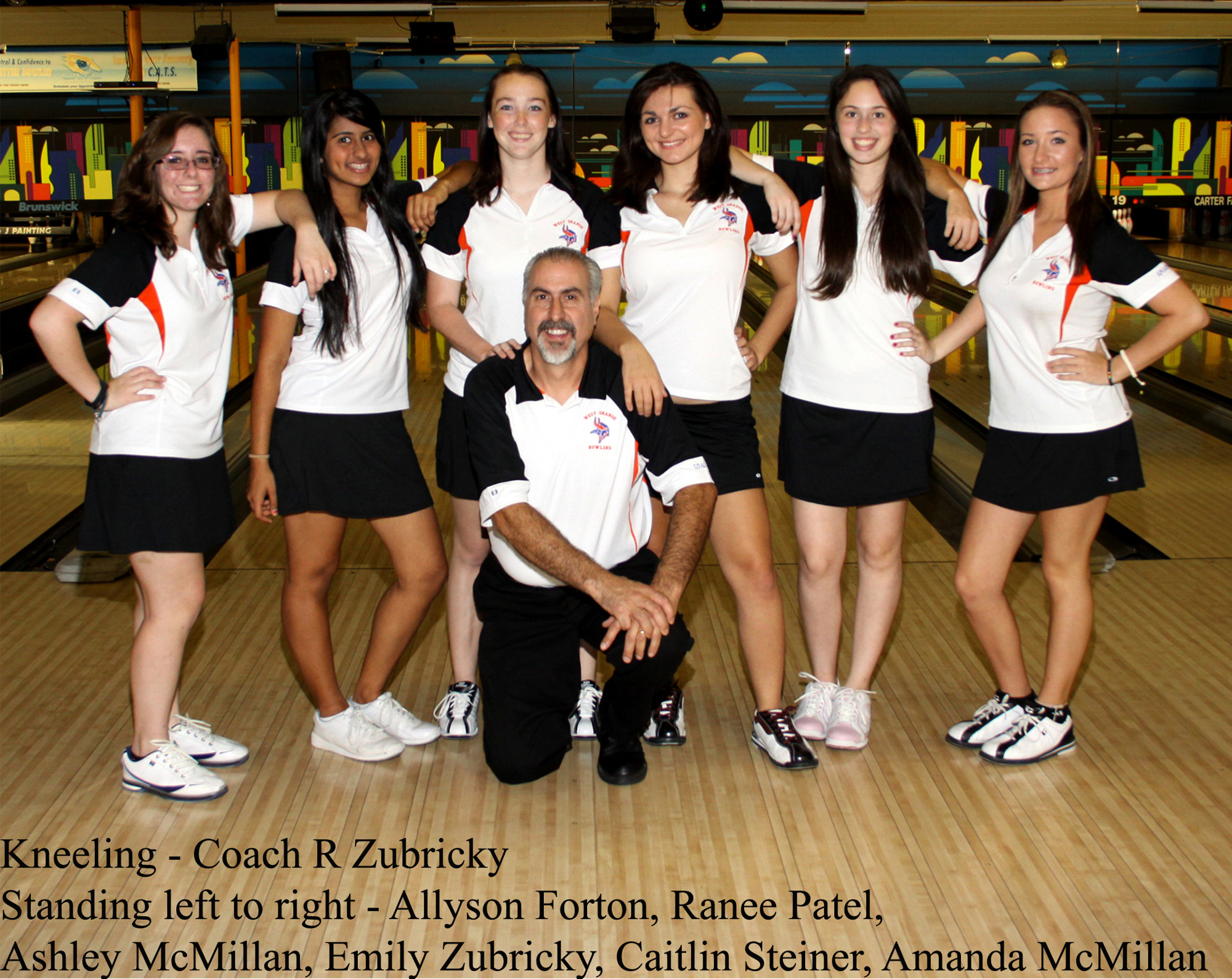

Zubricky said he is most proud of his years coaching the boys and girls bowling teams.

“I coached 28 years, and I think I have the most wins in West Orange history,” he said. “I got over 400 wins in 28 years. I’m an avid bowler. When Orange County decided to put varsity bowling into athletics — at the time our (athletic director) was Albert Saour — he said, did anyone know anything about bowling and I raised my hand.”

Both of his daughters, Emily and Madelyn, bowled for the Warriors, mastered their craft under their father’s coaching and went to Kentucky colleges on bowling scholarships.

And although he had just the two daughters at the high school, Zubricky said working at West Orange was like gaining another family.

“When people say family, it was a very tightknit family,” he said. “With the Keneipps, (Ron) Lopo, all that old crew, the Mulligans, Rick Stotler, Gary Daughtry, Pat Moran — it was a very tightknit group. And that stayed for such a long time. … All the teachers had each other. We knew each others’ spouses, we knew each other kids, all the teachers had their kids go to West Orange. … You don’t have that anymore.”

Zubricky is grateful for his long and successful career at West Orange, but he said he’s looking forward to retirement.

“I saw many teachers over the years stay around and never get to enjoy retirement,” he said. “I don’t have a specific plan, and I’m OK with that. I have some projects around the house. I like to build hot rods, like muscle cars, I have a 1970 Firebird, I have a 1969 AMX, and I have a 1923 Ford T bucket, along with some boats. I like tinkering on the vehicles.”

His wife, Joanne, has three more years of teaching before she retires.

“Somebody said I should open my own maintenance store or handyman service,” Zubricky said. “I don’t ever want to smell another piece of sawdust for the rest of my life.”